Paul Naschy (1934-2009) is, to some, the great unsung horror screen icon. An excessively prolific actor, writer, and director, Naschy has a credit on nearly one hundred productions over five decades of work in Spanish cinema. Vincent Price, Boris Karloff, Lon Chaney, Christopher Lee, and Peter Cushing have all received their fair amount of widespread acclaim, yet Naschy is only a household name in houses like mine (where the Tenebrae wall art is the classiest among those hanging because it features neither a throat slashing nor a rotted corpse). Why so, we ask? There are probably quite a few reasons: 1) though fairly well-known in his native country, it's understandable that his many films of variable quality aren't promoted as Spain's chief cultural export, 2) many of his films have been totally commercially unavailable since the heyday of VHS, and even then a good few of them have never landed on English-speaking shores, 3) although heavily indebted to the classic Universal and Hammer horror shows, Naschy's numerous spins on Gothic monsters and scenarios have a decidedly European flavor that, for some, can be difficult to digest. Gaudy, garish, sleazy, cheaply-made, and frequently illogical are all totally valid labels to place upon even the finest of Naschy's films (Hunchback of the Morgue, Horror Rises from the Tomb, Werewolf Shadow, El Caminante), but the most important adjective missing from such a list is "passionate." Naschy's films express a passion and adoration for classic monster movies that elevate them far above their occasionally shoddy production roots and end products. He was a man who made monster movies for the love of monster movies, producing them long after audiences stopped caring about the subgenre. He almost always cast himself in the lead roles, less out of narcissism or ego (though let's not say there isn't any of that fueling his work) than what came natural: being the screenwriter on most of his own monster films, it's fitting that he would be the only actor able or willing to step into the makeup again and again, always facing the risk of laughter or derision from horror audiences who, by the '70s and '80s, had moved on to bleaker, gorier, more lurid stock. Who else would dress up as the same werewolf in fourteen different films over thirty-six years? Only Naschy. So, in celebration of the life and work of Spain's horror legend (and a pretty smart way to allow me to queue up all those back episodes of the Naschycast that I've been missing out on), I spent 48 hours watching 12 previously unseen Naschy films. The highs were delightful and the lows were staggering, and here (in viewing order) are twelve chilly nightmares from the man who found such melancholy terrors a comfort.

Night of the Howling Beast (La malidcion de la bestia) (1975) dir. Miguel Iglesias

An anthropological team goes in search of a yeti, runs into a descendant of Genghis Khan, and has one of their crew, the famed Waldemar Daninsky (Naschy), get turned into a werewolf for the eighth time in his storied career. Night of the Howling Beast is a bit schizophrenic: it begins fairly obviously as a creature feature (see: lame opening yeti attack), segues into a supernatural cult film (with Naschy being held captive in the glowy cave from L O S T while two beautiful women take turns seducing him), and ends up somewhere closer to an adventure picture (with Daninsky, in non-werewolf form, dismantling Sekkar Khan's control over the region by heroically killing everyone in sight). In fact, this film is sort of an anomaly in the Daninsky canon when considering the fact that his personal battle with lycanthropy is relegated to secondary importance, probably because the film has so much going on otherwise (although, it's also fair to say that this divided attention affects each aspect of the story; take, for instance, the yeti, who shows up only in the first and last scenes. Let us call him Chekov's Yeti). The focus on the adventure elements is noticeable all over the place: the aforementioned lack of werewolf, the presence of a character named Wandessa who is not a witch or a vampire, gunfights, more deaths by duplicitous torture than monster mayhem, and a happy ending. That last piece is most jarring of all; Naschy's Daninsky films never have happy endings. The cure for Daninsky's particular brand of lycanthropy usually involves a loved one either shooting him repeatedly or sacrificing herself to destroy him at the moment he takes a big chunk out of her neck. This type of ending stresses the tragic nature of the character--a noble, self-sacrificing monster who must know love only to die by it. In Night of the Howling Beast, Daninsky's curse is broken by the horticultural powers of a magic flower, mixed with a little bit of blood from his ladyfriend (not even all of her blood; just a little! pfft). It's clear that, eight films deep, Naschy was looking to play around with his trademark character and try something a bit lighter. What could be fluffier than a climactic yeti/werewolf smackdown partially obscured by tree cover? As a perverse adventure film, it pretty much succeeds--we can call the many supernatural elements that crop up "additional flavors."

The Vengeance of the Mummy (La venganza de la momia) (1973) dir. Carlos Aured

Only two films in and I'm graced with a Naschy classic. I wouldn't rank The Vengeance of the Mummy among his best (a few too many issues with the script and production to grant it that level), but I would call it one of the better mummy movies I've seen. It's not a particularly inventive film, instead tending to follow the template outlined in the Universal and Hammer offerings, but it has the boon of an awfully violent and menacing villain. Mummies have generally been depicted in film as incredibly physical beings with great strength (playing in contrast to the often frail physical appearance of a bandaged thousands-year-old corpse), and Naschy's Amenhotep looms over them all as the most brutal--he's the type of petrified guy who will smash a young woman's skull to pieces (leaving behind what could best be described as "brain casserole") only to prove the point that his own bride should have a hardier constitution. Like most of Naschy's monster movies, Vengeance of the Mummy is a variation on the classic film tale with the exploitation knob turned way up, much to the pleasure of all. Director Carlos Aured is responsible for four Naschy collaborations in total (two of which--Horror Rises From the Tomb and Blue Eyes of the Broken Doll--are among his very best; another--Curse of the Devil--I'll be watching later in this marathon). All four of the Naschy/Aured films were completed in only two years (1973-1974) and, fittingly, they all display that same frantic pace in their storytelling. What's more noteworthy about their joint efforts is how stylish, unpredictable, and bleak they can be. It's easy to forgive Vengeance of the Mummy's rough edges (say, the repeated cuts to fast zooms closing in on a burn victim's face while a woman screams in response for far too long, Spanish-speaking Egyptians, or Amenhotep meeting his second doom because of his failure to duck a swinging bubbling cauldron) by the time it reaches its denouement, one falling easily amongst the grimmest I've witnessed. Unexpectedly, even after his defeat, Amenhotep emerges with a sort of victory, and what's worse than that is how quickly the survivors acquiesce to a phony story in order to avoid questions or complications. Brutal, bitter end.

Howl of the Devil (El aullido del diablo) (1987) dir. Paul Naschy

Howl of the Devil is an uncomfortable, off-putting film-- I think I liked it. Maybe I'd be better off saying "I admired it" or "I sat in awe of it." It's full of anger, vitriol, perversion, and unabashed misogyny-- although its premise is perfectly constructed for the inclusion of irony or satire, the film is uneasily free of both. No stranger to multiple roles, Naschy here explodes all reasonable limitations, playing something like (by my count) twelve different characters, including a set of twin brother actors and several of the major horror film baddies of the silver screen (Rasputin, Frankenstein's Creature, Mr. Hyde, Phantom of the Opera, Bluebeard, Waldemar Daninsky, Fu Manchu, Quasimodo, Zombie, Satan). One of the twin brothers, a washed-up alcoholic horror film actor, "commits suicide" before the film begins, and his more distinguished brother (he acted in Shakespeare!) wiles away his days by having his butler (the great Howard Vernon, here somewhat subdued) round up prostitutes that he can drug and play out elaborate costumed S&M scenarios with. Unfortunately, we watch as those same violated women are then murdered by a black-gloved killer. Who is the culprit? As writer, director, and star, Naschy is the guilty party. It's possible that this film is Naschy's most blatant ego-service, but at the same time it contains the seeds of a self-effacing, reflective glance backwards at a career that has been a disappointment (although he casts himself as a famous actor, there's also the admission that this actor was only "a nobody under his makeup" who wasted his life in horror movies; shades of JCVD) But, in other ways, the straight-faced horror aspects are abundant and the relentless misogyny is awfully tough to stomach-- if there is humor or commentary here, it's not simply at the expense of horror films but is actively rallying against them. When, at the film's conclusion, Naschy casts himself as the-actor-as-Satan, whose horror films have inspired a murderous rampage in his own son/the Antichrist (played by, who else, Naschy's real-life son, Sergio), what exactly are we meant to take away from all this? It's a film that seems torn by commingled self-delusion and self-hatred, resulting in a piece both fascinating and repulsive.

Fury of the Wolfman (La furia del Hombre Lobo) (1972) dir. José María Zabalza

Naschy's fourth outing as the perpetually-cursed werewolf Waldemar Daninsky is a poor showing, even if its premise sounds like a fair dose of mindless entertainment. I'm wary that the notes I took for this capsule review will make it sound better than it truly is. Daninsky is manipulated into wolfing out on his wife, ends up dead, and is then resurrected and mind-controlled by the a sadistic mad scientist, Dr. Ilona Ellman, of the nefarious Wolfstein clan. Even its constituent parts are appealing: creaky pseudo-science (Daninsky must use his beastly will to overcome the influence of the brain-seducing Chemitrodes!), requisite kinky Gothic S&M (Dr. Ilona ties up, whips, and otherwise tortures a bunch of circus freaks/failed experiments in her dungeon laboratory), and a more-than-usually morally questionable protagonist (let us not elide the fact that Daninsky intentionally uses his knowledge of his own werewolf affliction to dispose of his wife, forcing her into bed as the full moon rises overhead, gruffly informing her that he's about to make love to her like never before). But--all assembled--it's rough, hurried, and sloppy. Scenes jump around with little care for continuity or plotting (one werewolf attack in particular, on a sad pair of anachronistic peasants, was poached from an earlier Daninsky film). The story, particularly the Wolfstein family's back story, is needlessly convoluted and elongated (to the point where I'm not even sure we're given Dr. Ilona's motivation, beyond megalomania. I suppose she thought a werewolf would make a reliable pet?). Worst of all, Daninsky in werewolf mode hasn't an ounce of screen presence. He's filmed by Zablaza ambling about confusedly, as if he's perpetually unsure of his mark. For a werewolf film to have a boring, awkward werewolf is the greatest crime. Do, however, watch out for a soundtrack cue that very obviously rips off the Twilight Zone theme.

Assignment Terror (Los monstruos del terror) (1970) dir. Tulio Demicheli

The B-movie masterpiece that wasn't. Again, we have a can't-go-wrong concept that instead of going right or wrong goes nowhere. The film concerns a group of handsome aliens (lead by Michael Rennie) who descend to Earth from their dying planet and take over the bodies of some dead scientists. They decide to conquer the human race by resurrecting various folkloric beasts and creatures of yore, creating a veritable monster mash, because it sure will be easier to conquer those silly earthlings if they're frightened. I think that's why? Can't be sure; it's rather incredible how the exposition in a film like this eludes my every attempt at comprehension. Naschy is in this one as old faithful Waldemar and goes uncredited (some sources claim that he also plays the Frankenstein's Creature, but I'm less than convinced of this considering a) he's way too short, b) the actor under the Creature makeup looks nothing like him, and c) his dual presence would make certain scenes featuring both unnecessarily difficult. This does not strike me as the type of film that bothers taking the unnecessarily difficult route). Ostensibly the hero, Naschy has little to do here other than seduce a brainwashed female alien with his trusty musk and save the human species from badder alien invaders by beating up a feeble Mummy and Creature near the end, proving that werewolves possess not an ounce of sympathy. We are provided some groovy '60s flourishes, locales, and soundtrack cuts, but truthfully the film is more concerned with exhuming the graves of cheapo '50s sci-fi. We have the presence of Michael Rennie (The Day The Earth Stood Still) as a much more aggressive Klaatu figure, of course, but also all the kooky SF gadgetry that the aliens use, which in Naschy's scripting hands take on a perverted twist. The kinky brain-torture devices ensure that I won't be able to escape sadism this evening. Fittingly, none of the classic monsters go by their classic names, Naschy instead supplying them with knock-off sound-alikes (Tao-tet, Count de Meirhoff, Dr. Farancksollen). The mummy kills by hugging people. Whatever.

The People Who Own The Dark (Último deseo) (1976) dir. León Klimovsky

Somehow, the marathon's list randomizer knew that if I called it quits immediately after that hat trick of blandness, day two would be a struggle. So, in lieu of putting me through that, it shoots me an absolute gem under the title of The People Who Own the Dark (literal translation of Spanish title: The Last Desire/Final Desire). This one is an unconventional post-apocalyptic yarn set in the strangely intimate setting of (surprise) a sadistic pleasure villa for the incredibly wealthy. What's fun is that the film sets us up over its opening twenty minutes for something completely different-- we'd much sooner expect some giallo-style slayings to occur at the villa over a series of nuclear explosions in the distance, placing the villa's inhabitants into a Night of the Living Dead-styled struggle for survival, but it's the latter that the film turns to. It's an exhilarating decision, producing an engaging, suspenseful little number that doesn't have to go big and loud to convey its altered landscapes (both human and physical). The town in question exists outside of the blast radius, so the survivors are dealing the threat of encroaching radiation and mad villagers made blind by viewing the explosion, both of which are more repellingly effective than decimated buildings and smoldering bodies. The social criticism here-- the healthy wealthy stealing from and murdering the blind, directionless poor in the aftermath of a conflict that is obviously the result of the lechery and disinterested dealings of the powerful-- is a bit easy (as is the sort of justice dealt out by the blind mob throughout the third act and the government in the final moments), but it also adds a welcome layer of depth to the otherwise effective suspense scenario. Working with his frequent collaborator Leon Klimovsky, it's initially surprising that Naschy is here only in a prominent supporting role (and, to note, looks more burly and ruggedly handsome than usual). The film properly belongs to Alberto de Mendoza (of Horror Express and numerous gialli), who turns in a conflicted, sympathetic performance (more development of his character might have given the social critique the nuance it needed). Also, fun fact: in Horror Express, Mendoza plays a character who looks almost exactly like Naschy does in his Alaric de Marnac getup. This is a strong film and the perfect way to lop the head off of my first day. I'll be ecstatically surprised and pleased if any of the following films eclipse this one in my estimation. Which is all to say that Naschy works just as well (if not maybe sometimes better?) in other people's films.

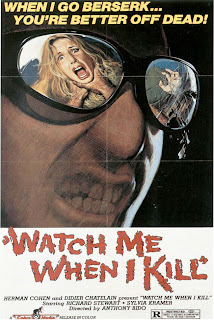

Exorcism (Exorsicmo) (1975) dir. Juan Bosch

Released only two years after Friedkin's The Exorcist in 1973, it's not as if Exorcism is obscuring its inspiration. That's okay, because it's also hardly a direct plagiarism if we discount its last ten minutes. But those final ten are particularly egregious-- a possessed girl spurting fluids (excess saliva rather than split pea soup), priestly hallucinations (best here: a snake head running out of a faucet in place of tap water), and a battle over the young woman's eternal soul (which here concludes in a tussle between the Reverend and a demonic dog, demonstrating that The Omen is ripe for swiping, too). It's too bad that Exorcism has this title, bringing along with it certain expectations that are fulfilled in the closing moments but fail to sync up to the otherwise interesting movie that had been unfolding prior. Because what's left when you strip away The Exorcist's influence is actually quite decent: a young girl gets into a car accident and starts acting peculiar and aggressive, Moreover, people close to her are ending up dead with their heads twisted 180 degrees the wrong way. Is the girl responsible? Has someone been hypnotizing her to commit evil deeds? Is there an actual possession or is that only what the real killer wants us to think? These are all questions the film posits, but any interest they could generate is deflected due to the fact that the film is called Exorcism, has that poster up there, and leads up to no more adventurous a conclusion than both the title and poster imply. Why spend so long building a mystery when there inherently isn't one? Casting some light suspicion on Naschy's Reverend Dunning seems a waste of time in this context, as does anything that comes before the young girl develops Linda Blair's skin condition and starts levitating-- which is too bad, because the former story was preferable. We are thrown a bone in the revelation of who is possessing young Lila, which is a gratifying answer that makes a bit of the previous hour and twenty worthwhile. Naschy is believable as the benign Reverend, even if he's a bit flat-- at least Father Karras had his mother issues. Recommended on the relative strength of the first hour alone.

Night of the Executioner (La noche del ejecutor) (1992) dir. Paul Naschy

We enter the '90s with this surprisingly enjoyable vigilante revenge picture that-- regardless of its actual decade of release-- belongs snugly among similar fare from the '80s, like Savage Streets, Class of 1984, The Exterminator, and the Death Wish sequels. Just listen to its opening theme-- a cross somewhere between Chopping Mall and bluesy jazz-- and try to convince yourself this is 1992. Another one that Naschy writes, directs, and stars in, Night of the Executioner sits so well with its earlier '80s brethren because of matters of content in addition to style. The exposition and character development are about as clunky as you'd expect in this sort of venture, bluntly communicating exactly as much information as you'd need to know in order to sympathize with the vigilante's plight (consider the opening sequence in a grocery store, where Naschy's vigilante and his family gush about how much they love each other on this day, his 50th birthday, as their future rapists/murderers leer on). The action elements are rough and gritty for a picture that came out in the same year as slick non-Spanish action films like Hard Boiled, Under Siege, and Universal Soldier, to the point where it's almost impossible to imagine these were made in the same universe, much less the same year. The film is also sleazy as can be; we have rape, strangulation, tongue-sawing, and castration. Moreover, Naschy's vigilante even goes through the signature Rocky training montage. And, no joke, there are actually characters in the film with the names Rocky and Rambo (Rocky being a young boy played, once again, by Naschy's annoying son Sergio, who rather unexpectedly and hilariously is gunned down near the film's end). Naschy is decent here and in impressive physical condition for his age, but I question the decision to remove his chatacer's tongue, hence making it a silent role. A neat touch in theory (a man who literally cannot communicate the injustice done to him through anything other than action) that is sort of ruined by the fact that Naschy's acting can be rather flat even when he's speaking. He fails to communicate much about his character other than mechanistic determination. Maybe that's appropriate? Anyway, its trashy qualities (signature quote: "I'd stick these beer cans in their elegant asses") fade away as it progresses, resulting in it ending up as a more-or-less standard crime film. Regardless, an enjoyable and competent romp from the man who would fill all roles if he could.

Curse of the Devil (El retorno de Walpurgis) (1973) dir. Carlos Aured

Another collaboration between Naschy and director Carlos Aured, and their sole Daninsky picture together. It's a good one, and the only Daninsky film I've seen that is decidedly a period piece (others mingle with the past in opening prologues, but always segue quickly into a contemporary setting). Furthermore, it's probably the most traditional werewolf picture that Naschy ever made, choosing to deal simply with a man's growing awareness of his lycanthropic affliction (there are no vampires, yetis, or Dr. Jekylls here-- Countess Elizabeth Bathory appears in the prologue, but only to bestow a curse upon the Daninsky family). This streamlining leads to a much more cohesive story than is usual for Daninsky films, while unfortunately dropping the wanton adventurousness of the other installments. While everything about Curse of the Devil is competent, we also have a fairly definite idea about where everything is heading, allowing a beleaguered viewer like me (already eight films deep) the guilty luxury of checking out mentally. I followed and enjoyed the film, but the impression it left on me was negligible. Its most enduring image is its last: a little boy's furry wolf hand clutched in his human mother's as they walk away from the camera. The Daninsky legacy will live on, and-- in the context of this marathon-- receive at least another chance to win me over...

Mark of the Wolfman (La marca del Hombre-lobo) (1968) dir. Enrique López Eguiluz

Which it immediately does. Mark of the Wolfman is Naschy's first Daninsky film and the one responsible for launching his career as a horror movie star. It also has the peculiar distinction of being (to my knowledge) the only horror movie to be filmed and projected in 70mm. Which paid off: it's a very nice looking film and contains the exact amount of stylish abandon that helps Naschy's monster films succeed. It's a werewolf vs. werewolf vs. vampire showdown with style to spare: see Daninsky's first transformation through some smudged plastic wrap over the camera lens, or the sudden reveal of the vampires in the dense fog of a train station. This isn't to say the film isn't occasionally sloppy-- I'm thinking particularly of a moment when the male vampire knocks over a vase with his cape. Ultimately, a fun film with a message no more complicated than "vampires are jerks." Naschy has a strong, youthful, brooding charisma in this one, managing to look stylish and attractive even when dolled up in a bonkers masquerade costume. More notably, his physical performance as the werewolf is remarkable in its intensity, containing a frantic and frenzied energy that is absent from his subsequent portrayals. It's a shame that the later growly, shambly Waldemars never learned to possess this sort of enthusiasm-- you can almost feel Naschy's glee to be in the makeup for the first time. It's a special moment.

The Frenchman's Garden (El huerto del Francés) (1978) dir. Paul Naschy

For my penultimate entry we take a look at a much different dramatic role for Naschy. Again here he is writing, directing, and starring, this time in a historical/biographical film about an actual casino/orchard/bordello owner who murders his especially wealthy patrons in order to collect enough money to purchase his land in his own name. While technically new ground for Naschy, he doesn't exactly play the role any differently than he would Daninsky or one of his giallo characters. Its a potentially complex character with a contradictory, sympathetic nature, but it seemed like Naschy's limited range (or, maybe more specifically, my pior exposure to Naschy's other performances) harmed its development. Moreover, the film is lensed exactly like any of his more conventional horror and suspense pictures would be (for example, to show the Frenchmen's inner turmoil at moments of high emotion, Naschy has a red light start pulsing over his blank face-- the exact same lighting trick he uses in similar situations in the supernatural El Caminante for his role as Satan-in-the-flesh). Worst of all might be its clunky, exposition-heavy opening ballad (it's horribly translated, but it can't be much better in Spanish) wherein the film's entire story and character motivation are laid bare, as if the film can't trust us to glean these details from the narrative itself-- I rarely find ballads appropriate even in Westerns, but here it's an even odder match, trying to talk up a tale about a small, pitiful man to mythic proportions. Perhaps a slave to historical accuracy, The Frenchman's Garden does arrive at a curiously undramatic climax and a queasy, prolonged final scene. Both of these scenes are confident and understated. Naschy steps up his game both in front of and behind the camera, leaving me with positive parting feelings for the film. What it really needs it a legitimate, restored release-- the beyond-degraded VHS source I viewed obliterated any visual or audio talent the film may have contained.

Night of the Werewolf (El retorno del Hombre-Lobo) (1981) dir. Paul Naschy

It's difficult to express exactly how wiped out I am as I approach this, our final entry in the event. Sitting through twenty-one gialli was a lot easier, perhaps because the variety was greater. In the case of this marathon, I'm on werewolf movie number seven, and it's not as if they're all that diverse from one another. I suppose that someone reading through these entries might find me overly critical of a man whose other films I have such a fondness for. But, I think what I've discovered is that a little bit of Naschy goes far-- I'm almost certain my opinions of some of these films would be more favorable if they had been spaced out from each other by a matter of weeks or months. That said, I'm also convinced that some of those I've watched in this marathon are of a lesser quality than those that I've enjoyed outside of its constraints-- a man makes a wagon-load of horror pictures, and one can't reasonably expect them all to be winners. I am pleased to report, however, that Night of the Werewolf definitely is. I'm watching the sadly-defunct BCI's Blu-ray release, which makes it far and away the nicest looking print of the past two days, giving my eyes a break from squinting. Besides the film being an unusually enjoyable semi-remake of Naschy's own classic Werewolf Shadow, Night of the Werewolf also has the honor of being released in 1980, the year before werewolves re-entered mainstream horror with An American Werewolf in London and The Howling. Those films' groundbreaking practical visual transformation effects and creature design would make Naschy's tried and true still-frame dissolves and furry suit look positively quaint and old fashioned-- outmoded, sadly. It's no shock that this was one of the last werewolf films that Naschy made, but its pleasing that he had such a successful final fling before the werewolf (the beast he had been ceaselessly and single-handedly resuscitating long after the horror genre at large had abandoned it) was to discover a new lease on cinematic life. I suppose I could talk more about the film's specific qualities, but why bother? This film is a farewell of sorts, to the fuzzy friend who made Naschy a star and to my movie-watching meltdown. So if you ever find the time, sit down, enjoy the pilfered bits from Stelvio Cipriani's Tentacoli soundtrack, and howl along.