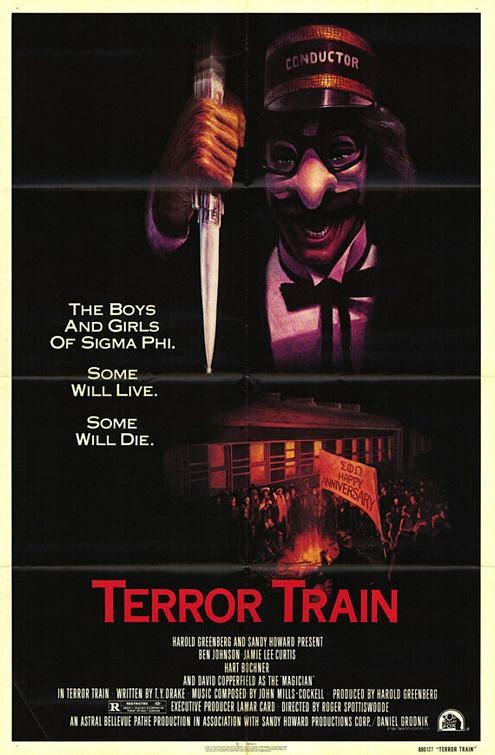

Logline: The boys of Sigma Phi Omega are throwing what might be the biggest party of their pre-med college careers. Well, if not the biggest, it's certainly the longest: this New Year's Eve costume party is taking place on a specially chartered train chugging across the frozen Canadian countryside, because that sounds like fun (and practical, to boot!). What the amassed party-goers haven't expected is that their isolated, locomotive night full of booze, sex, and magic might change onto deadlier tracks. Beneath one of the attendee's costumes lurks a stowaway, seeking revenge for the pranks of parties past. Before the train arrives at the station, he's determined to make them all scream louder than the train's whistle.

Crime in the Past: Exactly three years prior to the current action, the freshman class of the Sigma Phi Omega fraternity pulled a life-altering prank on Kenny (Derek McKinnon), their most nebbish of pledges. Doc (Hart Bochner), the frat's resident prank-puller and asshole, noticed Kenny's attraction to the lovely Alana (Jamie Lee Curtis), and so enlisted her and his fellow frat brothers to help him carry out a ruse aimed at humiliating poor Kenny. But not everyone involved in the prank knew Doc's true intentions, which were to get an unsuspecting (and underwear-ed) Kenny in bed with a dismembered, autopsied corpse. Doc and the gang flawlessly orchestrate the prank during the frat's annual New Year's bash, giving them all a good laugh at the end result (excepting that party pooper Alana, who screams in horror at her complicity). Then again, one supposes that the prank could only be considered a "flawless" prank if you disregarded the potentially perceived flaw of Kenny being so horrified at what has happened to him that he requires hospitalization for psychological and emotional trauma afterwards. But, come on, essentially flawless!

Bodycount: a serial magician makes 10 living people vanish, and 10 corpses reappear.

Themes/Moral Code: Terror Train is one of that rare breed of slasher films with a unifying theme informing its carnage, and the theme here is that of illusion. Though written only shortly after the beginning of the early '80s slasher boom, screenwriter T.Y. Drake's script is aware of how much weight films within the subgenre place upon misleading appearances and improbable plot points in order to further their not-always-well-conceived mystery and horror elements. Recurring slasher events such as the lightning-fast disposal of victim's bodies and the miraculous resurrection of the killer at the climax after certain death are here explained with tongue embedded deeply into grievous cheek wound: it's all magic! The casting of its killer as a professional magician allows the filmmakers to have a lot of fun playing around with the narrative cheats that most slasher films employ earnestly. Thus, when Terror Train imbues its killer with almost supernatural stalking and slashing abilities, it discourages us from critiquing it for fear of resembling those miserable souls who heckle magicians in the middle of their acts. The lapses in logic and violations of physics are all part of the act.

Additionally, the film also makes repeated use of the illusion of appearances, preventing the characters (and the audience) from seeing what's right in front of them. The costume party setting provides our killer with a perfect cover, allowing him to travel in plain sight and interact with his future victims while donned in the costumes of his previous victims. The killer makes numerous speedy costume changes over the course of the film, and this mutability of fixed appearance lends him a mysterious aura for both audience and characters, despite the fact that we're certain of his identity. Again, this is all in the spirit of fun, poking the conventions of the mystery-thriller genre in its ribs: for much of the second half of the film, we're encouraged with a knowing wink to consider the possible guilt of the obvious red herring, Magician Ken (David Copperfield), while the real killer Ken is standing beside him, cross-dressing as his red-haired assistant. The fact that this whopper escapes most viewer's discerning eyes on first viewing (I know it escaped mine) is a credit to the film's competency beyond the liberties we might afford it due to its emphasis on the illusory. It tricks us fairly and squarely, too.

Additionally, the film also makes repeated use of the illusion of appearances, preventing the characters (and the audience) from seeing what's right in front of them. The costume party setting provides our killer with a perfect cover, allowing him to travel in plain sight and interact with his future victims while donned in the costumes of his previous victims. The killer makes numerous speedy costume changes over the course of the film, and this mutability of fixed appearance lends him a mysterious aura for both audience and characters, despite the fact that we're certain of his identity. Again, this is all in the spirit of fun, poking the conventions of the mystery-thriller genre in its ribs: for much of the second half of the film, we're encouraged with a knowing wink to consider the possible guilt of the obvious red herring, Magician Ken (David Copperfield), while the real killer Ken is standing beside him, cross-dressing as his red-haired assistant. The fact that this whopper escapes most viewer's discerning eyes on first viewing (I know it escaped mine) is a credit to the film's competency beyond the liberties we might afford it due to its emphasis on the illusory. It tricks us fairly and squarely, too.

Killer's Motivation: Ostensibly, Kenny is seeking the psychotic version of comeuppance against those who humiliated him three years prior when they tricked him into becoming aroused by the cold, clammy embrace of a corpse. We're led to believe that Kenny's experience left him psychologically shattered and therefore susceptible to the desire for overblown retaliation. But maybe these motives are all an illusionist's misdirection: late in the film, we learn of the rumor that Kenny had been suspected of murder before the whole prank business transpired, and so might have already been a secret psycho all along, with the prank simply giving him a better excuse to stab people. Very tricky. A second alternative: as it's demonstrated that Kenny was always a student of magic, perhaps he's just homicidally pissed off that he didn't see the frat's sleight of hand (or, uh, bed) coming.

Final Girl: Oh, Jamie Lee. The woman who birthed the slasher subgenre's archetypal heroine in Halloween (1978) returns to the scene a few years later with a very different sort of final girl. Unlike JLC's other slasher roles (Laurie Strode [of Halloween] and Kim Hammond [of Prom Night]), the character of Alana isn't exactly an innocent victim of circumstance. Rather, she is an active, if uninformed, participant in the cruel prank that triggers Kenny's psychological breakdown. What sets her apart from the other prank participants (i.e. the killer's eventual victims) is her remorse. She's horrified and ashamed of her role in the prank, which provides immediate contrast with how everyone else involved experiences it: as Kenny is freaking out on top of the corpse-bedecked bed, rolling himself up in the bed canopy with his hysterical twirling, we see Alana scream while her friends belly laugh. Her remorse extends so far as to have her attempt a visit to Kenny in the psych ward shortly after he's admitted, and to have her chide her friends for years afterwards for their fond reminiscences of their heartless treatment of Kenny. When confronted by Kenny late in the film, Alana even attempts to apologize to him, which we feel is a genuine action on her part, unlike the pleading of some doomed slasher victims. This isn't to say that Kenny forgives her; if anything, he's probably just saving her for last. But the film obviously operates under some sense of karmic justice, and so Alana is spared because of her better qualities.

Evaluation: From the director of Turner & Hooch (1989) comes a film rife with magic, suspense, mystery, and 100% fewer dead dogs! But enough about Tom Hanks: Terror Train provides a wealth of slasherific pleasures. Inventive bloodshed, an implausible isolated location, an intelligent blending of mystery and magic, three iconic villain costumes, a young Jamie Lee Curtis screaming her heart out, and a gravely serious David Copperfield making peanuts serve themselves while grinding cigarettes through coins like the stud he knows he is-- these are but a few of the treasures that puff out of this one's chimney. To quote T.J. from My Bloody Valentine (1981), I'm "so damn sorey," but no one did this whole slasher thing better than the Canadians did in those halcyon days of the early 1980s.